In perhaps the biggest news story of the court’s current term, the Court ruled 5-4 in Rucho v. Common Cause that cases about partisan gerrymanders are non-justiciable, or unable to be decided, in federal courts because nothing in the United States Constitution or federal law mandates that parties have an equal right to representation and there is not a legally standard way of judging the political fairness of any proposed redistricting plan.

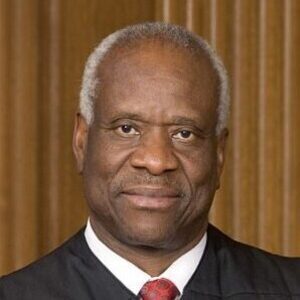

The majority opinion, delivered by Chief Justice John Roberts and joined by Justices Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Clarence Thomas affirmed that while “one person, one vote” remains a standard of law and that racially-biased districts are still illegal (as per the Voting Rights Act of 1965), there is no way for a federal court to judge how politically biased a district is, nor is there an agreed method to redress the issue if a plan were proven to be politically biased. Because of this, federal courts cannot rule on this issue.

The issue of “how much is too much” also arises. For example, no district will likely ever include a perfectly even number of Democrats and Republicans, so one party will almost always have an advantage if we also require districts to be compact and contiguous. Democrats are also more likely to live in cities, which means rural districts will lean Republican almost by default. The majority did allow that states and their constitutions may require politically neutral districts, as Pennsylvania’s state Supreme Court found last year, and that a future federal law or Constitutional amendment could change the Court’s opinion later on. This case ended the Court’s long stance of “punting” on partisan gerrymandering that had existed since Reynolds v. Sims established the standard of “one person, one vote” in 1964. Liberal observers were quick to note that this case was decided along party lines and in the first term after the Court’s conservative wing secured a majority.

The dissent, led by Justice Elena Kagan and joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Ruth Ginsburg, and Sonia Sotomayor, rejected the idea that this issue is unresolvable in the courts. Kagan’s dissent appeals to the Declaration of Independence that governments “derive their just power from the consent of the governed” and pointed to sworn testimony from a partisan gerrymandering case in North Carolina where an author of a redistricting plan named “Partisan Advantage” explicitly stated that he drew districts to elect as many Republicans as possible and the only reason he did not make more Republican districts was because there was no reasonable way of making a few urban centers like Charlotte or Raleigh entirely Republican. For balance, she also points to former Maryland governor Martin O’Malley’s stated intent to win as many House districts for Democrats as possible. Kagan also pointed out that the level of data available on party registration and voter behavior makes it easier than ever to draw districts with surgical precision that include voters loyal to one party and exclude others.

For Kagan, the simple fact that people have drawn districts in such a way as to maximize their party’s chances of winning means that we have a way to determine if a district is politically biased.

If someone can, with the help of GIS software, create a map that most favors Republicans in North Carolina, while holding to more broadly accepted standards about compactness and equal population, then the data processing abilities already exist to judge if a district benefits one party over another. That some states, such as Arizona and Iowa, have adopted commissions to redraw districts in a neutral fashion is of little help. Both North Carolina and Maryland, the states mentioned in this case, do not allow for referendums to change the state constitution, so a bill for non-partisan redistricting would have to go through a chamber already engineered to protect one party’s power. Even in states that do allow for referendums, such as Missouri, a ballot initiative for non-partisan redistricting passed there in 2018, but it was almost immediately ignored by the state legislature.

Voting rights organizations immediately registered their disagreement with the decision. Most feared that this opens the door for states to intentionally district themselves in a partisan manner. It may have the unintended side-effect of allowing racially biased districts to be argued for as merely partisan districts, which are now allowed. Conversely, arguments against partisan districts will now have to reframe themselves as racial discrimination to have a chance if they can even continue at all. Either way, gerrymandering will very likely explode in popularity and state legislatures chosen by these biased districts will have no reason to hide their aims. Essentially, to quote a phrase, it allows representatives to choose their voters, rather than voters to choose their representatives.

It now lies with state and federal lawmakers to end gerrymandering by law or to protect their power at any cost.